The main three indigenous berries around Point Hope, Alaska. (From L to R) Rubus chamaemorus (cloudberry), Vaccinium uliginosum (lowbush blueberry), and Empetrum nigrum (black crowberry). Photo credit: Joshua J. Kellogg.

As natural product researchers, field work is always one of the great benefits of our research that we look forward to and treasure. Accounts of famous botanists and explorers fuel our imagination and perhaps even prompt us to consider natural products as a career. Who hasn’t wanted to drag a GC into the middle of the Amazon, à la Sean Connery? I was similarly excited to embark on journeys to distant places; when I joined my graduate lab, my advisor Dr. Mary Ann Lila explained that the project I had originally sought to join, an International Cooperative Biodiversity Group (ICBG) project in Central Asia, was rapidly wrapping up with little chance of refunding. Her next project was in Alaska, had just been funded, and would entail at least one or two trips into the field.

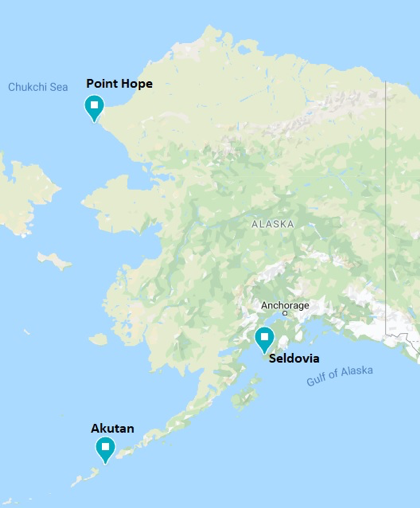

Our work was an EPA-funded project to investigate how climatic variations could impact the phytochemistry and health benefits of traditional resources. American Indian/Alaska Native (AI/AN) populations suffer disproportionately high rates of diabetes and obesity, primarily attributed to a shift from a traditional to more Western lifestyle. The traditional ecological knowledge (TEK) of these communities has long held that wild indigenous berries are a health-promoting resource, and so offered a culturally-relevant plant to investigate. To forge research partnerships, engage the community, and foster greater participation in the research project, we wanted to integrate tribal representatives in the bioassay research process by introducing a series of field-deployable assays to assess bioactive properties of berries. In order to sample from a varied climate as much as possible and gauge differences in the polyphenolic chemistry as well as the antimetabolic syndrome capabilities of these fruits, we partnered with three communities: Akutan, an island in the Aleutian chain; Seldovia, on the Kenai Peninsula, and Point Hope, a village far north on the Chukchi Sea (Figure 1). While each town and field expedition were unique, Point Hope stood out.

I had an indication of the remoteness of Point Hope as soon as we boarded our Cessna prop plane, when our pilot had to match the weight of the research team against the mail and canned good delivery so the plane could take off safely. The plane cruised over a crystal blue sea, the chalky white cliffs keeping to our right. We crossed back onto the land; a small grid of mostly prefabricated houses on a gravelly peninsula of land overlooking the sea appeared, with no roads emerging beyond the town. Stepping off the plane, feeling the wind rushing to greet us, crowned with salt and the high arctic sun sparkling on the water on three sides, we felt as if we were at the edge of the world. We dragged our belongings and equipment across the tarmac and lodged in a few empty classrooms in the local school.

A fundamental part of this project was engaging the community, but we were initially met with a healthy dose of skepticism. Some in the community felt we, non-Alaska Natives and outsiders (i.e., anyone not from Alaska), were there to either steal their knowledge or secret berry field locations, or somehow muck up their environment. Based on past interactions with other outsiders, this was not an unfounded concern. These communities have had their knowledge doubted and have had Western companies and developments wreak havoc on their communities, their environment, and their way of life.

Our goal to gain their trust was reinforced by the structure of the project, which placed them at the center of the research discovery process. By getting their hands on the bioassays and sharing in the process of experiment and discovery, we were able to forge an equitable partnership. We tested the berries for antioxidant potential, anti-glucosidase inhibitory activity, and other metabolically-related properties with students and some community elders as investigators, participating in the extraction and testing of their crops. The tone in the room changed when the elders and community members saw how our data conformed to their traditional knowledge surrounding the berries. Local participation enriched the research process and outcomes. Stories of harvests past, family traditions, and even recipes started flowing. Everyone wanted to share their variation of akutuq with us, a traditional dessert made from berries mixed with sugar, seal oil, and snow.

The next day we set out for collecting. The hills containing the berry thickets were a few miles away, with no roads or trails by which to navigate. We loaded up the ATVs and discovered a characteristic Alaskan fieldwork tool that most of us would not consider; nearly all of our guides carried rifles. Why? Bears. The bears are natural competitors for the berries, and the late summer season, when the berries ripen, coincides with the time when bears are most active in preparing for their hibernation, leading to semi-regular clashes with community harvesters; two weeks before we arrived someone had been mauled.

We roared down the beach, past whale bones and driftwood tossed onto the sand, and turned up to climb the ridge where the best picking lay. The collecting ridge looked over the tundra, ablaze with the warm colors of the turning foliage. All of these species are low-growing - the Empetrum nigrum (black crowberry) creeping along a few inches above the ground – so we lay on the tundra’s mossy carpet as we picked berry after berry, slowly filling our buckets. There was not a sound except the purring of the wind, and the elders with us shared stories of whale hunting from traditional boats, visits to the “south” (i.e., the lower 48 states), and favorite music (the Steve Miller Band came up surprisingly frequently). To break, we partook in more traditional trail snacks, the most memorable of which was the muktuk, preserved whale skin with the subcutaneous fat still attached.

The collecting continued until almost 10:00 p.m., but Arctic summer evenings stretch on forever, the sky turning salmon as the sun finally set after 11:00 p.m., and local kids played in the playgrounds until after 2:00 a.m. We returned each day to the school kitchen to clean and freeze the berries. Harvesting by hand was slow going, and it took several days to pick enough of each species to last us through the study. Our precious cargo was frozen and transported via a fish packing service in Anchorage.

Our stay in the far north drew to a close too quickly, though we would be back the following summer to share our results on the chemistry and detailed bioactivity data with the community. Point Hope was an incredible opportunity to blend participatory research and field bioexploration at the end of the world, and an experience I will never forget.

Core berry team on the tundra with the fruits of our labor. Pictured left to right: Drs. Courtney Flint, Josh Kellogg, Mary Ann Lila, and Gary Ferguson. Photo credit: Joshua J. Kellogg.

Core berry team on the tundra with the fruits of our labor. Pictured left to right: Drs. Courtney Flint, Josh Kellogg, Mary Ann Lila, and Gary Ferguson. Photo credit: Joshua J. Kellogg.

NEWSLETTER STAFF

Edward J. Kennelly, PhD

Editor In Chief

Patricia Carver, MA

Copyediting & Proofreading

Nancy Novick

Design & Production

Gordon Cragg, PhD

Mario Figueroa, PhD

Joshua Kellogg, PhD

Michael Mullowney, PhD

Guido Pauli, PhD

Patricia Van Skaik, MA, MLS

Jaclyn Winter, PhD

ASP Newsletter Committee

Contribution deadlines

Spring: Feb. 15; Summer: May 15 Fall: Aug. 15; Winter:Nov. 15

Please send information to

Edward J. Kennelly, PhD Editor In Chief,

ASP Newsletter

Department of Biological Sciences

Lehman College, CUNY

250 Bedford Park Blvd. West Bronx, NY 10468

718-960-1105

asp.newsletter@

lehman.cuny.edu

ISSN 2377-8520 (print) ISSN 2377-8547 (online)