Heinz G. Floss: PHOTO: UNIVERSITY OF WASHINGTON, DEPARTMENT OF CHEMISTRY, 1988

By Taifo Mahmud, PhD and Bradley Moore, PhD

On December 19, 2022, Heinz G. Floss, a world-renowned natural product chemist and a former president of the American Society of Pharmacognosy (ASP) and ASP Fellow, died at his home in Bellevue, Washington following a fall. He was 88 years old. Floss was a highly regarded mentor, proponent of natural product research, valued member of the ASP, and, to many of us lucky enough to work and study with him, he was an inspiration and a dear friend.

Floss was born on August 28, 1934 in Berlin, Germany. He grew up in a city ravaged by the Second World War and experienced the misery of the postwar era. He completed his Diplomarbeit (master’s thesis) (1958) in chemistry at the Technical University of Berlin and his PhD (1961) at the Technical University of Munich, both under the guidance of Prof. Friedrich Weygand. Weygand was a student of Richard Kuhn (Nobel Prize 1938), who was a student of Richard Willstätter (Nobel Prize 1915), who himself was a student of Adolf von Baeyer (Nobel Prize 1905). Baeyer was a student of August Kekulé, the principal founder of the theory of chemical structure and the Kekulé structure of benzene. Kekulé himself studied with Justus von Liebig. This illustrious scientific pedigree was very near and dear to Floss who prominently displayed a photo of Weygand in his office at the University of Washington. Like his mentors before him, Floss cultivated a pioneering spirit in his more than 150 students and postdocs, many of whom became university professors and leaders in industry.

One of his early graduate students, Laurence Hurley (PhD 1970 Purdue), recently recalled, “I once asked Heinz if he had any advice for an aspiring scientist and he answered, ‘Life is too short to drink cheap wine.’ After I thought about this, I realized this went much deeper than choosing the wine but represented Heinz’s philosophy about research too and unconsciously the most important lesson I had learned as a graduate student in his lab – choose important research questions to address.”

John Cassady, Varro Tyler, Heinz Floss, and James Robbers (l to r) at the 2000 ASP Annual Meeting in Seattle. PHOTO: COURTESY OF THE FLOSS FAMILY

Floss’s exposure to the field of natural products began when he worked on the biosynthesis of ergot alkaloids in fungi for his PhD thesis. This work was done in collaboration with plant biochemists Prof. Kurt Mothes and Dr. Detlef Gröger in Halle, East Germany. The work on ergot also acquainted him with Prof. Varro E. (Tip) Tyler, a prominent ergot researcher and one of the founders and the first ASP president. When Floss spent some time in Prof. Eric E. Conn’s laboratory at the University of California, Davis from 1964 to 1965, he and his family drove up to Seattle and visited with Tyler at the University of Washington. Subsequently, when Tyler became Dean of Purdue University’s School of Pharmacy in 1966, Floss joined its Department of Medicinal Chemistry as an associate professor.

Floss was a highly regarded mentor, proponent of natural product research, valued member of the ASP, and, to many of us lucky enough to work and study with him, he was an inspiration and a dear friend.

Floss’s close relationship with Tyler and his love of natural product research placed him among active members and leaders of the ASP community. He was the ASP president from 1977- 1978, during which time he played a major role in expanding the ASP Newsletter. A decade later in 1988 he was the second recipient of the ASP Research Achievement Award, which years later was renamed in honor of ASP’s second president, Norman R. Farnsworth. “As a recipient of the award he (Floss) became one of the first ASP Fellows in 2006,” reflected Gordon Cragg, former Chair of the ASP Fellows. “Among his many other honors, he held honorary doctorates from Purdue University and the University of Bonn in Germany.” In 2000, Floss organized a memorable ASP conference in Seattle where, as young PIs, we helped him set up one of the first ASP symposia on natural product biosynthesis during the early days of microbial genomics. He was always pushing the limits of his biosynthetic studies to incorporate the latest technology and trends and, as such, helped challenge and shape the ASP to be a progressive Society. In his 1977 address as the incoming ASP president, he wrote these prophetic words: “We have to look to the future and define new goals and frontiers. Areas like the genetics of microorganisms producing natural products, the development of economically viable systems for the production of higher plant constituents by single cell culture, or ultimately even by bacterial fermentations using recombinant DNA technology, for example, are all highly significant and legitimate research areas in Pharmacognosy.” Floss ends with saying that “the opportunities which this field offers are truly boundless, but whether they are realized depends entirely on each and every one of us.”

ASP President Amy Wright noted, “Dr. Floss was truly a pioneer in natural products research whose work and mentoring has touched all of us in the natural products community. His dedication to defining and rigorously addressing groundbreaking and challenging questions will remain an inspiration. Although he is gone, his influence will continue through his publications and in the hands of the many researchers who had the opportunity to learn from him and who in turn are passing along this legacy of excellence to the next generation. The ASP will greatly miss this giant of natural products research.”

Floss’s close relationship with Tyler and his love of natural product research placed him among active members and leaders of the ASP community.

Floss’s approach to science was ingenious and thorough. He was intrigued by how plants and microbes construct their bioactive and often complex chemical structures. Using his unique ability to solve intricate biochemical problems, he illuminated many of the foundational metabolic processes that we take for granted today in natural product biosynthesis. He was also fascinated by the stereochemical control and the catalytic mechanisms of enzymes.1 Floss was a master of combining chemical and biochemical approaches to solve questions in biology. To understand the control of chirality in enzyme-catalyzed reactions, he and his team stereoselectively synthesized methyl groups, labeled with the three hydrogen isotopes, and used them in biochemical assays to tease apart the intricate fate of a substrate during the course of an enzymatic reaction.2

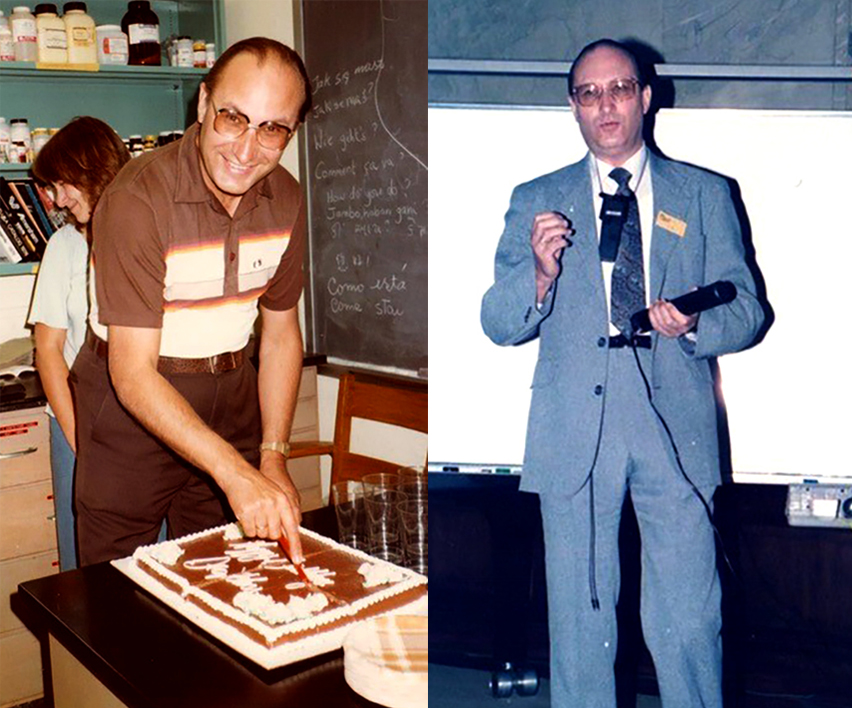

Left: A Floss birthday at work. Right: Floss in lecture mode.

His former graduate student Ming-Daw Tsai (PhD 1978 Purdue) noted, “In addition to natural product chemistry, biosynthesis, and pharmacognosy, Heinz Floss was a world leader in using chiral methyl groups to probe the mechanism of enzymatic reactions. I had the chance to work on such problems as his PhD student during 1975-78, which set the foundation for my future career in stereochemistry and enzymology. Even more importantly, I learned from Heinz to give students a great deal of freedom in research, to treat them as friends, and to explore interesting problems with new methods.”

Floss was among scientists of his generation that used interdisciplinary approaches, employing sophisticated isotope labeling studies and a variety of state-of-the-art biological methods including molecular genetics to study the biosynthesis of bioactive natural products. After 16 years at Purdue, he moved to Ohio State University to become Chair of the Department of Chemistry. There he started incorporating molecular genetics into his research, often with his microbiology colleague William Strohl. At the time he also published an iconic paper in Nature with the groups of Sir David Hopwood and Nobel Laureate Satoshi Omura on the “Production of ‘hybrid’ antibiotics by genetic engineering.”3 That paper is regarded as one of the earliest demonstrations of mixing and matching genes from biosynthetic gene clusters to engineer the production of new to nature natural products. In 1988, he moved to the University of Washington in Seattle, where his group continued to study the biosynthesis of a variety of important natural products, such as acarbose, ansamitocin, asukamycin, rifamycin,4 Taxol, thiostrepton,5 and validamycin.

What made Floss’s lab such an exciting place to work and study during his Seattle years was how he approached projects, often matching chemists with biologists. Not only did this approach allow for projects to be examined in detail from a variety of perspectives but also allowed for the transfer of knowledge and training between group members. Sunghae Park (PhD 1999 Washington) reminisced, “Looking back on my time at Dr. Floss’s lab, I feel extremely lucky that I had a chance to be trained as an independent thinker. The lab was full of brilliant postdocs and senior grad students with diverse expertise, from organic synthesis to molecular biology. He encouraged us to learn from each other and come up with our own solutions.”

“We have to look to the future and define new goals and frontiers. Areas like the genetics of microorganisms producing natural products, the development of economically viable systems for the production of higher plant constituents by single cell culture, or ultimately even by bacterial fermentations using recombinant DNA technology, for example, are all highly significant and legitimate research areas in Pharmacognosy.”

Celebration of Heinz Floss’s 75th birthday in Xiamen, China, August 2009. Sitting (l-r) - Jürgen Rohr, Isao Fujii, Inge and Heinz Floss, Lutz Heide and son. Standing (l-r) - Linquan Bai, Kenji Arakawa, Chang-Joon Kim, Jae Kyung Sohng, Taifo Mahmud, Yuemao Shen, Bradley Moore, Lutz Heide’s wife and other son. PHOTO: COURTESY OF YUEMAO SHEN

While Floss excelled in science and commanded excellence, he was often most proud of the independent achievements and careers of his former students and postdocs. He thus took great pleasure in helping his mentees achieve and surpass their career goals. He was respected and appreciated for his never-ending encouragement of their scientific curiosity and independence, as well as for helping them navigate challenges in their careers. Andreas Kirschning, a postdoc from 1989 to 1991 in Seattle, recalled a defining conversation with Floss that set him off to his successful 30+ year academic career in Germany where he is now a professor of organic chemistry at Leibniz University Hannover. Kirschning reflected that Floss’s “genuine personal interest for his coworkers led to large academic natural product schools around the world. I remember a brief conversation with him, a ‘click’ moment of my life. He asked, ‘Andreas, what do you plan to do after your postdoc time in my lab?’ And I responded that I’d probably go into the pharmaceutical industry. He then asked if that was what I really wanted to do, and I recall saying that I’d prefer going into university but that I didn’t think that I was good enough for that. Heinz responded, ‘You have what it takes, I believe in you! Do it!’”

“The opportunities which this field offers are truly boundless, but whether they are realized depends entirely on each and every one of us.”

One of his early postdocs John Vederas put Floss’s contributions to mentorship well when he said, “The legacy of a professor is in the education and long-term inspiration of new researchers, who then transmit this in their own way to the next generation. In this regard especially, Heinz has been a true grandmaster who has educated a host of accomplished scientists and profoundly influenced the way a very large field of science has developed.”

loss enjoyed traveling the world and regularly visited his former group members and his many collaborators who often became close personal friends. One of his long-time collaborators and friends Professor Eckhard Leistner from the University of Bonn remarked, “Heinz was an exceptional natural product scientist. In addition, he was also a very friendly and modest person. It was easy to approach him and to talk to him. This may be one of the reasons why he was an outstanding educator, teacher, and a friend I am proud to have had.”

In summer 2005, soon after Floss closed his lab at the University of Washington, he gave an inspiring symposium lecture at the ASP annual meeting in Corvallis, Oregon, summarizing his 45 years of natural product biosynthesis research. In his lecture, not only did he elegantly describe the depth and breadth of his decades of exceptional research, but also humbly shared how he set himself up to a highest standard by trying to follow the almost impossibly rigorous standards of Prof. Duilio Arigoni at the ETH Zürich. In his words, “I would always ask myself whether a particular experiment or proof would meet Arigoni’s standards. If you choose a role model, you might as well pick a challenging one, even if you can never live up to it.” A review article describing his life-long scientific career entitled “From Ergot to Ansamycin – 45 Years in Biosynthesis” can be found in J. Nat. Prod.6

Floss was a master of combining chemical and biochemical approaches to solve questions in biology.

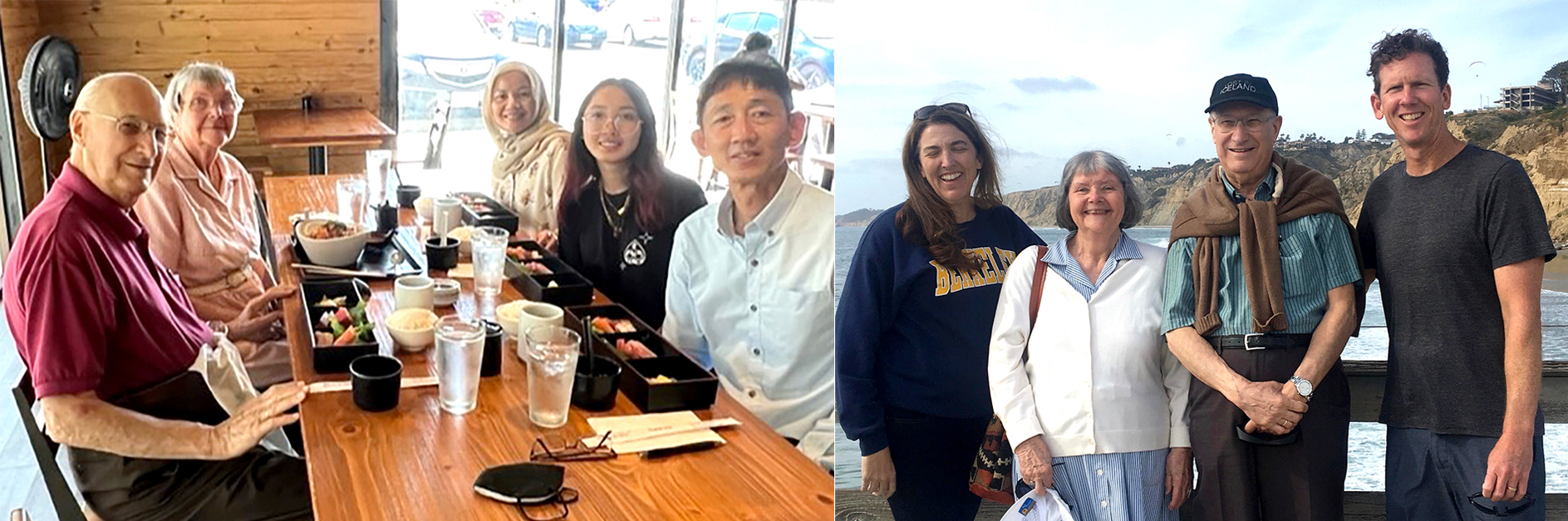

Above left: Celebration of Heinz Floss’s 88th birthday in Bellevue, Washington, August 2022, just a few months before he passed away. Left to Right: Heinz Floss, Inge Floss, Shinta Muljani, Reika Mahmud, and Taifo Mahmud. PHOTO: COURTESY OF TAIFO MAHMUD. Above right: Heinz and Inge Floss (center) with Brad Moore and his wife Sonia Teder-Moore in May 2019, at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography Pier at UC San Diego. PHOTO: COURTESY OF BRADLEY MOORE

A special side of Heinz Floss that many of us marveled was his remarkable and magical relationship with his beloved wife of 66 years, Inge. They were inseparable and regularly traveled together on work trips that took them across the globe. Their admiration of Native American art, Asian culture, and the great outdoors were some of their passions that they enjoyed together. After his full retirement in 2005, they regularly visited friends and colleagues in Europe and Asia as well as drove around the country to visit historical sites and enjoy the natural beauty. One of their favorite places was Kyoto, Japan, where they visited nearly every November (except during the COVID-19 pandemic) to enjoy the red-tinted maple leaves in the fall (momiji). Just weeks before his death, they were finally able to return to Kyoto, Japan, together, for the last time.

Floss is survived by his beloved wife, Inge, his sons, Peter (Barbara) Floss and Helmut Floss, his daughter Hanna (Tony Andrews) Floss, nine grandchildren, and four great grandchildren.

Floss was among scientists of his generation that used interdisciplinary approaches, employing sophisticated isotope labeling studies and a variety of state-of-the-art biological methods including molecular genetics to study the biosynthesis of bioactive natural products.

LITERATURE CITED

- Floss, H.G. Stereochemistry of enzyme reactions at prochiral centers. Naturwissenschaften. 1970. 57: 435-442. doi: 10.1007/BF00607727.

- Floss, H.G.; Tsai, M.D. Chiral methyl groups. Adv. Enzymol. Relat. Areas Mol. Biol. 1979. 50: 243-302. doi: 10.1002/9780470122952.ch5.

- Hopwood, D.A.; Malpartida, F.; Kieser, H.M.; Ikeda, H.; Duncan, J.; Fujii, I.; Rudd, B.A.M.; Floss, H.G.; Omura, S. Production of ‘hybrid’ antibiotics by genetic engineering. Nature. 1985. 314: 642-644. doi: 10.1038/314642a0.

- Yu, T.W.; Shen, Y.; Doi-Katayama, Y.; Tang, L.; Park, C.; Moore, B.S.; Hutchinson, C.R.; Floss, H.G. Direct evidence that the rifamycin polyketide synthase assembles polyketide chains processively. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1999. 96: 9051-9056. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.16.9051.

- Mocek, U.; Zeng, Z.; O’Hagan, D.; Zhou, P.; Fan, L.D.G.; Beale, J.M.; Floss, H.G. Biosynthesis of the modified peptide antibiotic thiostrepton in Streptomyces azureus and Streptomyces laurentii. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1993. 115: 7992-8001. doi: 10.1021/ja00071a009.

- Floss, H.G. From ergot to ansamycins – 45 years in biosynthesis. J. Nat. Prod. 2006. 69: 158-169. doi: 10.1021/np058108l.

Vol 59 Issue 1

NEWSLETTER STAFF

Edward J. Kennelly, PhD

Editor In Chief

Patricia Carver, MA

Copyediting & Proofreading

Nancy Novick

Design & Production

Gordon Cragg, PhD

Mario Figueroa, PhD

Joshua Kellogg, PhD

Michael Mullowney, PhD

Guido Pauli, PhD

Patricia Van Skaik, MA, MLS

Jaclyn Winter, PhD

ASP Newsletter Committee

Contribution deadlines

Spring: Feb. 15; Summer: May 15 Fall: Aug. 15; Winter:Nov. 15

Please send information to

Edward J. Kennelly, PhD Editor In Chief,

ASP Newsletter

Department of Biological Sciences

Lehman College, CUNY

250 Bedford Park Blvd. West Bronx, NY 10468

718-960-1105

asp.newsletter@

lehman.cuny.edu

ISSN 2377-8520 (print) ISSN 2377-8547 (online)